How I Rewrite Recipes

A thing that I do when I cook is to re-write the recipes I’m using (whether they’re from a cookbook or my own invention) onto a piece of paper in a very specific way. I think the approach I use is handy, so I’m describing it here in case you’d like to use it. (Or in case you need more evidence about how weird I am.)

There are 4 ideas that I think are important:

- Copying the recipe, by hand, forces me to think through the steps and keeps me from not noticing something important. (“Step 7 – soak a thing for 24 hours…” :sob:)

- Putting the ingredients in the order I’ll cook them, next to the method and timing, keeps me from having to flip back and forth.

- Putting preparation steps next to the ingredients, rather than up-front, usually helps me separate preparation (mise en place) from the actual cooking.

- Being concise is good. Most recipes are wordy, but you only need all the words the first time you read the recipe.

These come about from two major inspirations. One is the Cooking for Engineers blog. The author, Michael Chu, uses tables to indicate how to combine ingredients:

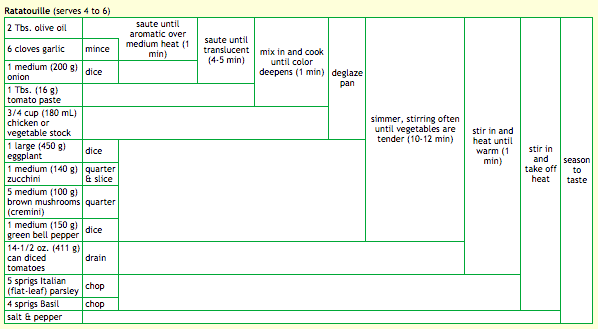

Ratatouille from Cooking for Engineers

In the above recipe, from this page (where he also has a verbose, photo-heavy alternative approach), you can clearly see the steps, which proceed from left to right, and indicate how to group ingredients or intermediate stages, until you season to taste. This is a very clever approach, and I like its terseness.

The other inspiration is the classic Joy of Cooking recipe style. In the photo below from a 1970s edition, the ingredients are interleaved with instructions on how to use them, rather than listed above the steps.

No of course I haven’t made the Joy of Cooking recipe for porcupine…

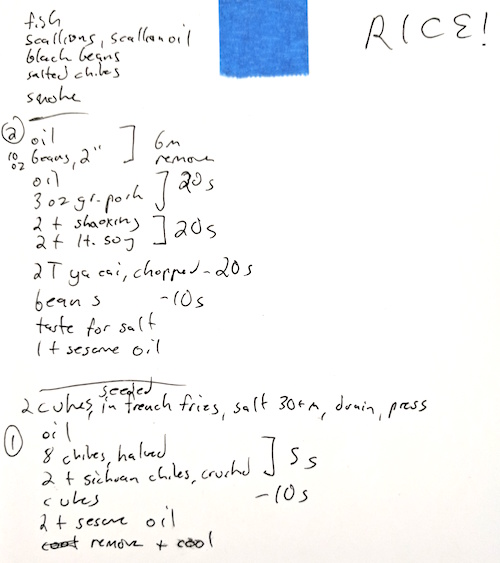

Given these two influences, here’s what a recent set of my notes for cooking a Chinese dinner look like:

Smoked Fish, Sichuanese Green Beans, Sichuanese Cucumber

I cooked four things: rice (in a rice cooker), a smoked fish dish (which I’ll write about some other time), and two recipes from Fushia Dunlop’s outstanding Sichuanese cookbook, Land of Plenty. The first of them (marked with a 2, as a reminder to cook it second), is the best of example of what I try to do. Each ingredient is listed, with just enough information to prep correctly: 10 oz beans, 2" , or 3 oz gr. pork. Things that are added together are bracketed. Timing or cooking notes are next to the brackets. Once you start applying heat to things, everything happens in order.

The cucumber recipe doesn’t quite follow the rules, as I give a prep step for salting the cucumbers and letting them sit as a separate line. And the fish dish doesn’t follow the approach at all, but only because it’s a simple recipe I know well, and I just wanted to remind myself what ingredients I was using. (The rice is in all caps so I don’t forget about it!)

Compared to the Cooking for Engineers approach, recipes written out this way are more linear, and are sequentially vertically rather than horizontally. Compared with the Joy of Cooking approach, recipes are terser and written around what you do to the ingredients, rather than in paragraphs. And compared to them both, the process of writing before you cook is integral. I don’t think I’d publish a recipe using this style – the extra words of explanation are helpful when you’re trying to communicate with a reader. The act of figuring out how to write a recipe in this way, in the minutes before you start dicing onions, keeps at least me prepared and on-track.

If you try something like this, please let me know how it goes! (And if you try any of the recipes above, same!)