On How and When to Teach Layers of Abstraction in Programming

This post was originally published on Medium

There’s recently been some interesting opinionated writing in the R statistical programming community about how and when to teach the abstracted, easy-to-use approaches to solving problems, versus the underlying nitty-gritty. David Robinson, Data Scientist at Stack Overflow, wrote a blog post recently called Don’t teach students the hard way first. The primary example was on the data-manipulation tools in the tidyverse, versus the underlying methods in base R, but the discussion was mostly about principles in pedagogy. Some highlight quotes from the original article (which I recommend reading!):

that phrase keeps popping up: “I teach them X just to show them how much easier Y is”. It’s a trap…

feeding students two possible solutions in a row is nothing like the experience of them comparing solutions for themselves…

students should absolutely learn multiple approaches (there’s usually advantages to each one). But not in this order, from hardest to easiest…

one exception is if the hard solution is something the student would have been tempted to do themselves.

And some comments and responses I found particularly interesting:

If there’s an educational purpose for a long and short way, then just be honest from the get-go: “There [is] a shorter way to do this, which I’m going to show you next, but I’m first going to show you the long way since I want you to understand X” — where X is a theoretical point, not nostalgia. — **Joyce Robbins**

So, teach easier first, unless the harder is more obvious; teach usefulness first; teach the familiar first. All of this makes sense, and I’d like to expand on it a bit, not to disagree, but to try to clarify why I agree so much.

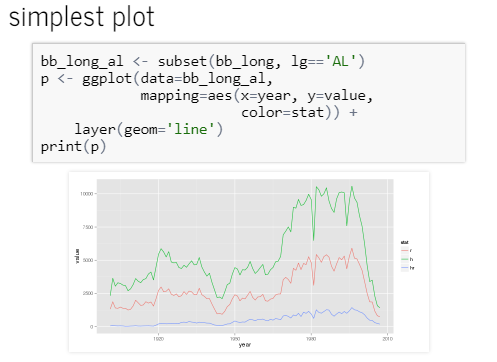

In R, I certainly agree with David and others in the specific case of the tidyverse , but I’ve previously weighed in on a related issue, taking the other side. In 2010, I wrote a blog post about ggplot2, the extensively-used data visualization library, and the ways that its design was both amazing and confusing. In particular, I criticized author Hadley Wickham’s pedagogical approach in his book on ggplot2, specifically specifically his introduction of the qplot shortcut early on. Subsequently, I’ve given several presentations about ggplot2 where I started at the lowest level of abstraction, the layer, and built up higher levels of abstraction and short-hand over the course of the talk. It’s worth noting that nobody ever uses this lowest level of abstraction in practice, but I thought it worthwhile to show how to construct a graph using that approach, before introducing the shorthand that everybody uses.

Was I wrong about that? I’m not sure. I want to make a case that both tidyverse-first (in the case of data manipulation) and layers-first (in the case of ggplot2 specifically) are the right answers. To rescue any hope of consistency on my part, I need an answer to the following question:

What is a general principle that would help us determine what to teach first?

Option 1: Teach the low-level nitty-gritty first, and then build on layers of abstraction. This is inconsistent with my advice — the tidyverse is not the low-level nitty-gritty. Note that in programming more broadly, this might mean teaching assembly language (hardware) and LISP (math) first, then high-level languages later. This approach is a popular way to build technical experts with deep understanding in, say, university departments, but it can be intimidating to many beginners. I don’t think this is the right answer in general, and certainly not for statistical programmers.

Option 2: Teach the layers you’ll use in practice first, then dive under the hood later. This is also inconsistent with my advice — nobody uses layers directly in ggplot2. In programming more broadly, this would be like teaching working examples in Javascript and Python first, then working backwards to explain why the code works. This is highly appealing to new learners, as you get to see some results quickly. But learning this way can feel like magic, and it often requires a difficult shift in thinking later on. (See also…) > the tidyverse tends to be more consistent than base R — Hadley Wickham

Option 3: Teach at the layer of abstraction that is most self-consistent and has the clearest metaphors. The tidyverse has excellent, clear verbs for explaining what’s going on with data processing, and is generally self-consistent and complete. Additionally, it maps well to peoples’ understanding of what you can do with data in spreadsheets or other statistical data systems, especially if they’re familiar with SQL. There’s some magic in non-standard evaluation and bare names for things, but it can be hand-waved for a while without too many problems, and it’s only really surprising for experienced programmers.

Similarly, the layers approach to writing ggplot2 is self-consistent and complete, and has minimal magic — the inferences that make writing advanced ggplot2 fast and elegant have to be manually written out. But you can (and definitely should) learn the shortcuts and “slangy” abbreviations later.

Does this framework — teach the self-consistent metaphors first — make sense? Any readers with a background in learning theory have a critique? I think this is what Dijkstra suggests in the article that Shog9 linked to, at least if the thing to be taught is not “radical novelty”: > It is the most common way of trying to cope with novelty: by means of metaphors and analogies we try to link the new to the old, the novel to the familiar. Under sufficiently slow and gradual change, it works reasonably well; in the case of a sharp discontinuity, however, the method breaks down: though we may glorify it with the name “common sense”, our past experience is no longer relevant, the analogies become too shallow, and the metaphors become more misleading than illuminating. This is the situation that is characteristic for the “radical” novelty.

Thanks to Merav Yuravlivker and David Robinson for comments!